The Uncomfortable Gift: How ‘The Road Less Traveled’ Redefined My Map

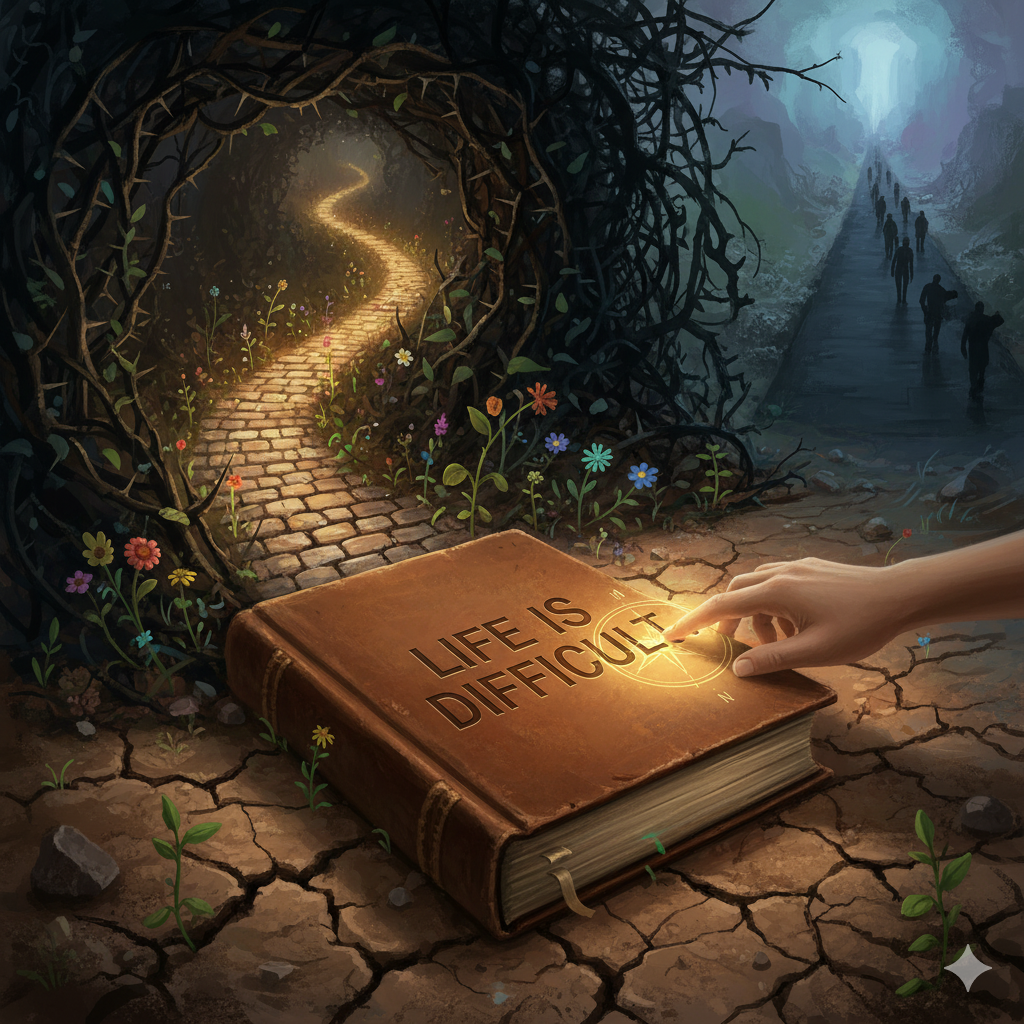

There’s a certain kind of book that finds you exactly when you need it. It doesn’t always arrive with a flashy cover or a booming recommendation. Sometimes, it’s sitting quietly on a dusty shelf in a second-hand bookshop, or in my case, on my nightstand, looking profoundly serious with its stark, typographic cover. The book was M. Scott Peck’s “The Road Less Traveled,” and its famous opening line felt less like an introduction and more like a direct challenge to everything I thought I knew: “Life is difficult.”

I was in my early twenties. And my entire philosophy, though I wouldn’t have admitted it, was the exact opposite. I believed life was supposed to be straightforward, and if it wasn’t, you were probably doing it wrong. I was navigating the early map of adulthood, a map I assumed would have clear paths, signposts, and a guaranteed destination if I just followed the rules. Peck’s first sentence was like someone calmly, kindly, tearing that map in half.

This book didn’t just change my perspective; it gave me a new set of eyes. And it started by giving me the gift of a truly uncomfortable truth.

The Liberation of Embracing the Grind

Peck’s central thesis is that the moment we truly accept that life is inherently difficult—that it is a series of problems—it ceases to be so difficult. This wasn’t pessimism. This was the most liberating realism I had ever encountered.

Before this, my approach to problems was a cycle of avoidance, frustration, and self-blame. A challenging project at work, a strained friendship, a personal goal I wasn’t meeting—each wasn’t just a problem to be solved; it was a personal failing, a deviation from the “easy life” I was entitled to. I was spending so much energy being angry that the problem existed, I had none left to actually solve it.

Peck introduced me to the concept of discipline as the essential tool for navigating these difficulties. His four pillars—Delaying Gratification, Acceptance of Responsibility, Dedication to Truth, and Balancing—were not just words; they were practical tools.

- Delaying Gratification was about learning to eat the frog. To structure my pain and my pleasure. It was the simple, profound act of doing the hard thing first, not because I was a martyr, but because it made the rest of the day taste sweeter.

- Acceptance of Responsibility was a gut punch. He drew a clear line between those who neurotically blame themselves for everything and those who characterologically blame everyone else for anything. I saw myself, and others, in that spectrum instantly. It forced me to ask, constantly, “What is my responsibility in this situation?” This question alone dissolved a million petty grievances.

This section of the book reframed struggle. It wasn’t a sign that I was lost. It was the very terrain of the journey. The path wasn’t about avoiding the rocks and the mud; it was about developing the right boots to walk through them.

Love is Not a Feeling; It’s an Action

This was perhaps the most profound shift the book engineered in me. Like most people, I had a Bollywood-ified, feeling-based definition of love. Love was the butterflies, the overwhelming emotion, the “can’t live without you” intensity. And when those feelings inevitably faded or fluctuated, I worried the love was gone.

Peck offered a definition that was so startling in its simplicity that it initially felt cold: “The will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth.”

Love is an action. Love is a choice. Love is work.

This rewired my brain. It meant that love wasn’t something you just fell into; it was something you built. It applied to romantic relationships, yes, but also to friendships, to family, and critically, to the relationship with myself. It meant that showing up for a friend when I was tired was an act of love. That having a difficult, honest conversation was an act of love. That setting boundaries to protect my own well-being was an act of love.

It demoted the fleeting feeling of “being in love” and promoted the steady, enduring practice of loving. This took the pressure off. Relationships weren’t magical, fragile things that would shatter if the feeling waned. They were living structures that required continuous maintenance, and that maintenance itself was the love. This was a quieter, less glamorous understanding of love, but it was a thousand times more durable and real.

The Grace of a Unifying Spirit

The final section of the book, on grace, was the part I was most sceptical about. I’ve always had an ambivalent relationship with spirituality. But Peck, a psychiatrist, approached it not with dogma, but with a scientist’s curiosity for the unexplainable.

He talks about grace as the powerful, unconscious force that promotes our evolution, our growth, often in ways we can’t see or understand in the moment. He speaks of serendipity, of unexpected help, of the power of the unconscious mind.

While I didn’t adopt his specific Christian framework, this section gave me permission to believe in something larger than my own conscious will. It allowed me to acknowledge the role of mystery, of synchronicity, of the countless times a solution appeared from nowhere after I’d stopped straining for it. It was the final piece of the puzzle: we must exercise our discipline and our will (our map), but we must also be open to the grace that sometimes redirects our path in ways more beautiful than we could have planned.

The Map I Use Today

“The Road Less Traveled” didn’t give me all the answers. No book could. But it gave me a sturdier compass and a more honest map.

It taught me that the road less travelled isn’t a hidden path that only a special few find. It’s the main road that everyone is on, but many are walking with their eyes closed, complaining about the bumps. The “Road Less Traveled” is simply the road travelled with eyes wide open, with a commitment to truth, and with the courage to embrace the difficulty as part of the journey.

I still have my old, yellowing copy. I don’t re-read it often. Its lessons are so deeply embedded in my daily thinking that I don’t need to. It’s the silent operating system running in the background of my life. When I choose to do the hard thing first, that’s Peck. When I approach a relationship as an active verb and not a passive feeling, that’s Peck. When I face a problem and my first thought is, “Okay, this is difficult. Let’s begin,” instead of “Why is this happening to me?”—that is the enduring, uncomfortable, and utterly priceless gift of that book.

It was the first book that treated me like an adult. And in doing so, it helped me become one.